Richard Berk

Violent crime recently has been increasing in the United States. Although data from the Uniform Crime Reports are complete only though 2020, local data that now are available suggest that in many areas of the country, violent crime increases have continued into 2022. There also have been several recent mass shootings, defined by four or more deaths from a single shooting incident. Mass shootings account for a tiny fraction of all homicides but add dramatically to the visibility of gun violence.

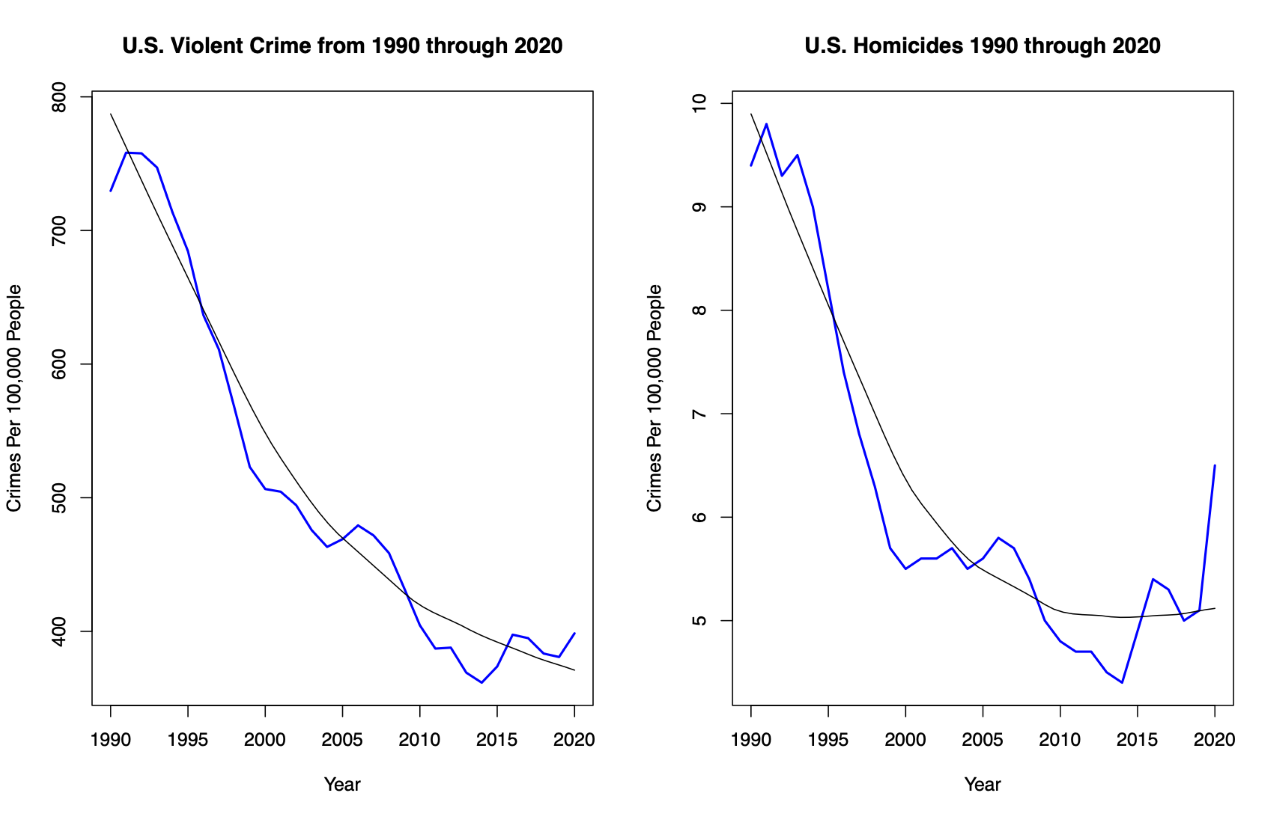

Every homicide is a tragedy, but recent crime rates actually are modest compared to some earlier decades. The plot above on the left shows the crime rate for crimes of violence from 1990 to 2020. The blue line is plotted from the actual numbers, while the black line is a smoothed version with small year to year variation averaged away. Clearly, the violent crime rate was nearly twice as high in the 1990s compared to the past several years. Yet, there apparently is an uptick in the data starting about 2014. Is that the canary in a coal mine? The smoothed line does not show any uptick. That will be addressed shortly.

Homicides are a very small proportion of all violent crime, although they account for much of the public’s concerns about violence. Their trends can be masked by the overall trends in crimes of violence. The plot above on the right shows only the UCR homicide rate from 1990 to 2020. The number of crimes per capita is far smaller, but the tends look about the same. The uptick after 2014 looks relatively more dramatic. However, the increase is only about 2 homicides per 100,000 people. And again, the smoothed line shows no uptick.

Taking to raw numbers at face value, recent increases in homicides and violent crime have been attributed to three factors: (1) COVID public health measures such as travel restrictions, school closures, lockdowns, and curfews, (2) COVID sickness and death itself, and (3) less aggressive police practices in response on Black Lives Matter and other organized criticisms of police use of force. Let’s consider each in turn.

The increases in violent crime in general and homicide in particular began in 2014, well before the events associated with two of the three explanations. COVID-19 began spreading toward the end of 2019 and officially arrived in the United States early in 2020. Shortly after, it became the third leading cause of death for the country as a whole. For Blacks and Hispanics, life expectancy fell by about 3 years. For Whites, it was by about 1.2 years. Various public health measures were introduced beginning in the early spring of 2020. The pandemic and the public health measures that followed no doubt disrupted day-to-day life and increased substantially life’s burdens, especially in disadvantaged neighborhoods. There is good reason to think that existing resentment increased and new resentments were created. Surges in violent crime might follow. But the timing does not work unless one focuses only violent crime increases from the middle of 2020 perhaps through 2022. For most of that interval, UCR data are not yet available and are not included in the two figures.

The timing for explanations building on Black Lives Matter might be a better fit. The social movement first gained visibility around the death of Trayvon Martin and the acquittal of George Zimmerman in 2012 and grew with the deaths of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, Eric Garner in New York City and others. A nearly singular emphasis on the use of force by police was galvanized in 2020 with the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chavin. Subsequently, the large demonstrations in 2020, coupled with property damage and threats of violence by a few, gradually eroded much popular support.

What might Black Lives Matter have to do with recent increases in violent crime? Perhaps the most plausible speculation begins with a claim that the demonstrations, combined with widely publicized criticisms of police practices, led to less aggressive police tactics. Some moderation in the use of force could result from well-meaning responses to past excesses, while some police officers might simply choose to abstain from any encounters for which they might be later criticized, fired, sued, or criminally charged. Whatever the truth behind such conjectures, one consequence might be to embolden individuals already inclined toward violence; public criticism of the police might be seen as delivering the proverbial get-out-of-jail-free card. The timing of this explanation could fit the facts, but it is far too early to marshal evidence one way or another.

Even though the increases in violent crime tend to be concentrated in neighborhoods that already had substantial crime problems, the violent crime increases appear to be quite common throughout the county. Some local district attorneys are progressive, and some are not. Some local mayors and governors are Republicans, and some are Democrats. Some state legislatures lean left, and some lean right. Political finger pointing at the state, county and city level will not likely be persuasive. Blaming individuals or institutions at the federal level probably will not work either because most crimes are not federal crimes, and federal actions can only have local effects at the margins.

One is left with several conclusions. First, the recent violent crime increases, even if they are not just noise, are dwarfed by the amount of violent crime in the 1990s. We have not returned to the bad old days. Second, the speculative explanations commonly proposed must fit the timing of the recent violent crime increases. Conjectures revolving around the COVID-19 pandemic and pent-up frustrations, at least as usually formulated, do not seem to get it right. Third, explanations based on more passive police practices, real and imagined, coupled with the perceptions of reduced risk among individuals already predisposed toward violence, may have some merit, but the existing data range from weak to nonexistent. It is very difficult to bring facts to bear. Fourth, if one takes the solid black curves in the two graphs at face value, we have been on a time path that is bottoming out. Sadly, this may be about as good as it gets under the existing conditions that affect violent crime. Variation in violent crime over the past few years may be nothing more than a bit of bouncing off the bottom. Fifth, with the passage of time, and the accumulation of better data, we may understand more about what drives violent crime. But we have a long way to go.

Finally, one must always be wary of drawing strong conclusions about crime trends from the Uniform Crime Reports (UCR) or any of the usual crime data. In particular, a shooting is usually the root cause of a homicide. But whether a shooting actually leads to a death depends a lot on happenstance, such as whether any vital organs are hit, on the quality of medical care, and on how soon that care begins. The quality of medical care for gun-shot wounds has improved dramatically over the past 20 years. That may have reduced the proportion of shooting victims who become homicide victims. At the same time, one has to wonder about a growing lethality in the firearms readily available to shooters. The Saturday night specials of days gone by have been replaced with 9mm semiautomatic Glocks, Colts, Rugers, and Sig Sauers. Shooting victims these days may be more difficult to save. Yet, these countervailing trends, and more, are obscured in conventional crime data. It is very hard to understand the reasons why violent crime goes up or why violent crime goes down.

References

Abrams, D.S., “COVID and Crime: An Early Empirical Look” (2020) U of Penn, Institute for Law & Economic Research Paper No. 20-49, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3674032 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3674032

Dehkordi, A.H., Alizadeh, M., Derakshan, P., Babazadeh, P., and Jahandideh, A. (2020) “Understanding Epidemic Data and Statistics: A Case Study of COVID-19.” Journal of Medical Virology 92: 868—882.

Dunedin, Z.O., Yan, H.Y., Ince, J., and Rojas, F. (2022) “Black Lives Matter Protests Shift Public Discourse.” PNAS https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2117320119

Francis, M.M., and Wright-Rigeur, L. (2021) “Black Lives Matter in Historical Perspective.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 17: 441—458

Sorenson, S.B., Sinko, L., and Berk, R.A. (2021) “The Endemic Amid the Pandemic: Seeking Help for Violence Against Women in the Initial Phases of COVID-19.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence: 36 (9-10): 4899—4915.